Jacky Lansley

STARTING POINTS

Crossing Paths

In 2016 I began to work with a group of performance artists on the theme of boundaries – of race, class, gender, sexuality, age – and how these boundaries might be explored through an interdisciplinary creative form which would celebrate difference while finding common ground. To do this we chose to start with personal stories. In my first meetings with the artists I invited them to choose a story that was either joyful, mundane or distressing and it was significant how each chosen story, whatever the starting point, contained all three emotional perspectives. We called this research ‘Crossing Paths’.

About Us

In 2018, with some of the same artists and some new to the process, we continued this exploration of otherness through personal and political stories, which became a performance research project called ‘About Us’. In our performances of About Us there were episodes, which didn’t seem to connect – moments that might seem obscure, but which, we hoped, provided enough clues for audiences to go on a journey with us. Jreena Green talked about the way her Mother used to stand, Esther Huss sat in the street trying to decide whether to have a hot or cold shower, Tim Taylor investigated the pleasure of chance encounters through song and Ingrid MacKinnon talked about the joy and love for her infant son. The technique of the dancer/cricketer Fergus Early’s spin bowling was scrutinised on film and movement images inspired by tennis were performed live and on film in a derelict tennis court in Hackney, London. These multiple and random ‘stories’ become a kind of celebratory collage – glimpses of personal human lives that many could relate to – and through this experience we began to explore deeper concerns and questions about ‘us’ – what is it to be human and what is our relationship with the other species we share the planet with?

This led to us exploring an embodiment of certain animals – the elephant, giraffe and parrot in particular – in the studio and in performance. We studied films and images of these animals to explore their essence, rather than mimicking them, and to find connections, even similarities, with our own human animal reality. This research continued and in early 2020 we formed the ‘We Are Animals’ research project.

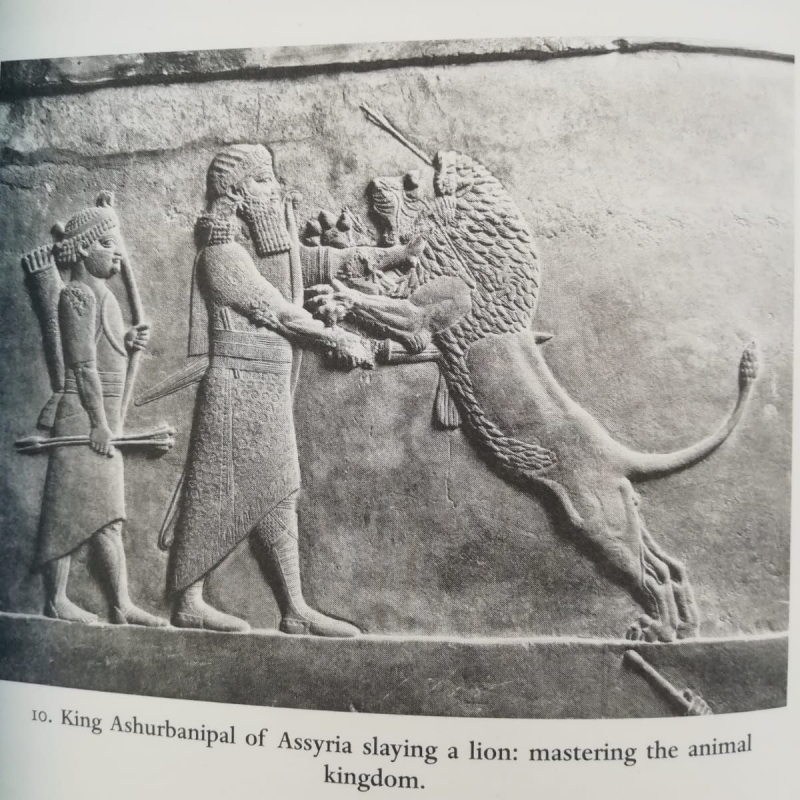

An image of ancient man dominating the animal kingdom (around 2500 BC)

By contrast this neolithic cave painting depicts the insignificance of hunter gatherer humans, shown as undefined stick creatures alongside the magnificent physical detail of the bison and antelope.

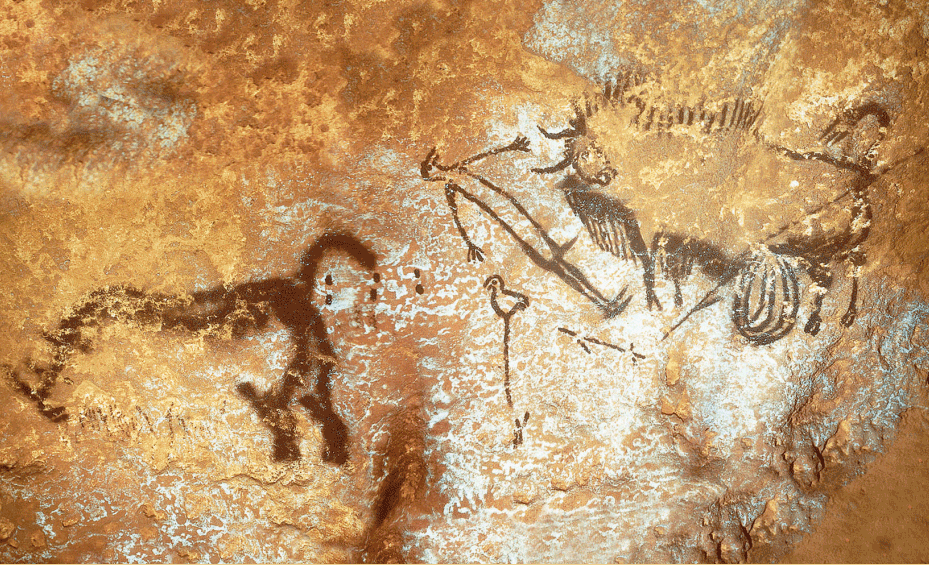

African Grey Parrots flocking and foraging in the wild.

MORE STARTING POINTS

In his book’ Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow’ Yuval Noah Harari asks these questions:

What is the difference between humans and all other animals?

How did our species conquer the world?

Is Homo Sapiens a superior life form, or just the local bully?

Harari is a historian and he uses this discipline to beam a light on our pre history:

“Anthropological and archaeological evidence indicates that archaic Hunter-gatheres were probably animists: they believed that there was no essential gap separating humans from other animals….

Such an animistic attitude strikes many industrialised people as alien. Most of us automatically see animals as essentially different and inferior. This is because even our most ancient traditions were created thousands of years after the end of the Hunter-gatherer era.”

His book continues to discuss the historical journey and ultimate horrors of modern animal domestication – factory farming etc. [are we ‘domesticated’?]- and what this means ultimately for ourselves….asking the question ‘how will we protect this fragile world from our own destructive powers?’. The discussion about the domestication of animals drew me to a personal story about parrots. I grew up with a pet parrot, quite literally, as parrots live a long time. She was called Susie and she was an African Grey – though you couldn’t tell, as she constantly plucked her feathers and was very bald; this is a classic neurotic symptom of tamed, caged animals. Domestication is not the same as taming. A domestic animal is genetically determined to be tolerant of humans. An individual wild animal, or wild animal born in captivity, may be tamed—their behaviour can be conditioned so they grow accustomed to living alongside humans—but they are not truly domesticated and remain genetically wild. Susie, for example, would bite given any opportunity. She adored my Father but seemed intolerant of others. She lived her whole life as an isolated parrot, and while she made a variety of what seemed happy vocal sounds, like all pet parrots she was living a distorted and very limited life. It was only very recently that I discovered the African Grey parrot in the the wild lives in large flocks and can fly many miles each day. They spend hours foraging for a variety of natural foods, socializing, communicating, bathing, preening, establishing nesting territories, mating, excavating nests, and raising their young. Even with lots of stimulation, life in captivity is absolutely nothing like the life parrots evolved to live in their natural habitats. See the following article for detail about how wild parrots live, and what happens to them in captivity:

‘The True Nature of Parrots’ by Denise Kelly, Joan Rae, and Krista Menzel

African Grey parrots are very popular as pets because they are assumed to be highly intelligent and ‘talk’. Their status is currently endangered and the illegal exotic pet trade, driven by demand from primarily the west, is driving them to near extinction. A new study shows that the birds have almost disappeared in Ghana, where they once flourished. Many other species are nearly extinct, owing to loss of habitat, climate change and the pet industry. Some species have gone from the planet forever. We are animals too – and we need the other species we share the planet with to survive ourselves. If they go, there is much evidence that we will go also.